One afternoon, I was sitting pressed to the window, siphoning wi-fi from the cafe across the alley, reading an article on my laptop. It was about a young woman, about my age (at that time, she and I were in our early 20s) who had become bedridden due to fatigue, if I recall. And without even thinking about it, I sighed heavily and said “ugh I would love to be bedridden.”

My then-boyfriend was, um, not exactly understanding. He turned from his giant monitor across the room with a look of disgust and the kind of confusion that only a white man with loving parents who has never really had a struggle, like, ever, can experience.

“What? Why would you want to be bedridden???”

I didn’t bother explaining. Let me tell you about my life at that point. I was unmedicated, working two jobs (cocktailing at night, assistant manager at a coffee shop in the morning) and a wholly unpaid internship in the remaining time. I had not had an entire day off work in at least six months. I’d been leasing the world’s tiniest studio in a Jacobethan brick building that was built in the 1920s and hadn’t really had a lot of updates since. Most mornings I was up in the dark and returned home in the dark. My coffee shop pay check covered the rent, just barely, and I was a frequent flyer at the local food bank. When my boyfriend moved in with me (for, honestly, unknown reasons), he brought an enormous drafting table, an upright bass, and no income to speak of for several months.

Which is to say: The idea of just laying in bed for a prolonged period of time sounded like a vacation. A vacation that I could almost afford, because it didn’t require going anywhere. I think at that time, I just really wanted someone to help me, care for me, take care of some of the bullshit of being 22 and on your own.

In the same way that I’d often dreamed, when I was 20 and eating licorice in a custodian’s closet, of being institutionalized, now I would fantasize about lying in a hospital bed, crisp sheets tucked neatly around me, learning to knit until I was too exhausted to knit anymore and then, I would take a little nap with my knitting draped dramatically across me.

I’m not saying this is rational. I’m just saying that sometimes, when life is really overwhelming, and there are just way too many things to do, it sounds nice to do dick-all for a while and let some of these other dipshits in your circle pick up the slack.

Which is why I’m not surprised that one of the therapies applied to people who were experiencing symptoms of schizophrenia — which is really a lot to have going on in one’s head — as well as depression and mania was just to let them sleep it off. Or rather, make them sleep it off. A little bit at a time.

Dr. Sakel’s special sleepytime

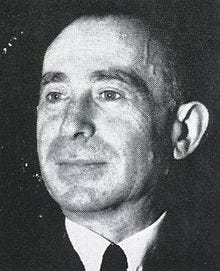

Born in 1900, Manfred J. Sakel was a bright kid who went on to become a bright adult. Both a neurophysiologist and psychiatrist (hell of a one-two punch), Dr. Sakel got his start in Vienna and later worked in Berlin, but was forced to flee to the United States to escape the Nazis in his 30s.

Earlier in his career, Dr. Sakel had hoped to make psychology more scientific. In a 1938 paper he wrote on his treatments, he explained that he desired “for psychiatry to come closer to medicine and for medicine to become more closely associated with psychiatry.” One way that he did this was to use medications to try to cure, rather than simply treat the symptoms of, mental illness.

He initially found success sedating opium addicts who were withdrawing by delivering high doses of insulin. Insulin shock was easier to bring about than other sorts of medically-induced comas, and it could be easily lifted by increasing the blood sugar. While going through the legitimately awful experience of opioid withdrawal, people could essentially sleep it off.

Later, he expanded this treatment to people with psychological conditions, like depression and schizophrenia. Patients of Sakel’s were able to experience a kind of micro-coma that would put them under for an hour or two, after which they would be revived, “shocking” the systems, both mental and physical. Because that was what Sakel was really after. He wanted to re-orient the mind/body connection.

Here’s his writing on this treatment, circa 1938:

“We may first think about what constitutes the mind as we know it. Its manifestations in the form of thoughts, emotions and actions are the result of an organization and classification of many simple sensations. There are possibilities in such organization for changes in quality as well as degree. With no sensation, we can have no mind, yet clinically we deal with severe disorders of function and various degrees of mental deterioration when all senses are intact. The patient may feel, taste, smell, hear and see, and yet be unable correlate some or all of these elements into more complex systems or there maybe inadequate emotional responses showing that there has been a change in the quality of such organization.”

His theory, then, was to sync up the parts of the mind and body through a full-system reset. It was basically like when you bend a paperclip open and jab it into the little circle on the back of an electronic device.

The treatments were very labor-intensive for the staff and workers at the hospital. Because the insulin had to be administered a little at a time, most days of the week, several times a day, the patient received nearly round-the-clock care, enjoying small (15 minutes) or longer (an hour) comas throughout the day. As a result a lot of the patients were more well-off, so Sakel became a kind of Coma Doctor to the Stars.

Dr. Sakel’s insulin comas were pretty popular throughout the next several decades — because also WHO DOESN’T WANT TO BE BEDRIDDEN. REALLY. — and, even when they caused convulsions, memory loss, and other significant side-effects (like, uh, death), patients “frequently express ‘a feeling of being reborn.’”

It also had a pretty strong reputation. According to a 2000 study of the practice, “between November 1934 and February 1935 he published thirteen reports claiming an improvement rate of over 88%.”

The end of an era

Dr. Sakel died in 1957 of a heart attack — and his treatment went not long after. The evolution of psychotropic drugs, ECT, and the general understanding that maybe putting the body through three dozen bouts of hypoglycemia isn’t great for you, insulin shock treatments became less and less common.

There’s another reason that inducing a coma isn’t especially popular anymore: It’s not a very reliable treatment. Later research found that while people felt better afterward (again: BEDRIDDEN), the longterm social recovery was pretty low. And again, there’s that whole risk-of-death thing. And also, with the outrageous cost of insulin (that’s a different ball of wax completely), it’s not the most economical use of a drug.

I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty sure I would still accept a treatment of just staying in bed all day. But then again, I’m literally writing this from my bed so, I guess dreams do come true.