I don’t drink gin. This is in part because I think it’s gross, and in part because when I was 19, my boyfriend was 21 so he was in charge of the alcohol buying and he literally only drank gin and we often mixed it with Crystal Geyser Juice Squeeze for reasons that can never be fully explained.

Anyway, I have no use for gin. Which means I also have no use for tonic. And I mean really, none of us do because there are much better cures for malaria and also we are not pirates. But some people like tonic — they like the bitter-and-yet-floral-and-yet-sweet flavor of it. And they like it with gin because that’s what their brains are used to now.

What’s interesting — and relatively recent! — is that when I say “tonic,” you know exactly what I mean. That’s because “tonic” has become pretty well standardized; it’s quinine, it’s soda water, it’s sugar, it’s some other shit probably. But when you order a gin and tonic, the bartender reaches for the soda gun and you’re both on the same page.

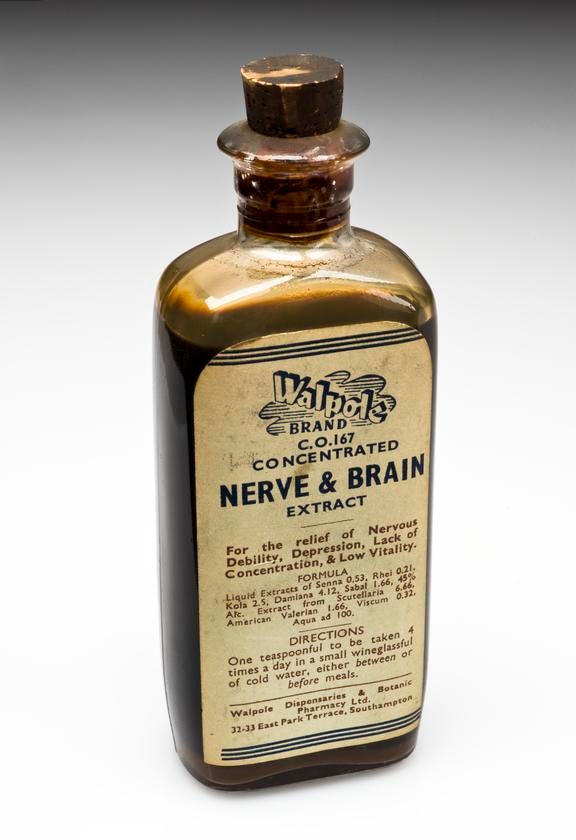

This has not always been the case. Tonic, as we know it today, was formerly merely one of many, many tonics. Because a tonic wasn’t an agreed-upon beverage. It was basically anything that someone could patent and sell over-the-counter from the druggist as a medicinal treatment. And hoo boy, tonics really did include anything! And they really did promise to cure, well, anything. “Nerves”? There’s a tonic for that. “Melancholy”? We’ve got a tonic! Uterus on the mosey? T O N I C.

But a really especially fun fact about a lot of tonics, particularly those which proclaimed to cure depression or other mental ailments, was that they were made of poison. Like actual poison.

Take one spoonful of rat poison and call me in the morning

The first thing to note is that it wasn’t just mental patients who were getting the arsenic treatment. Oh no. Poisons — including belladonna, digitalis, strychnine, arsenic, and others — were frequently used to treat everything from colic to cancer. Warts? Rub poison on them. Bronchitis? Put some arsenic in a cigarette (YES REALLY) and light it up.

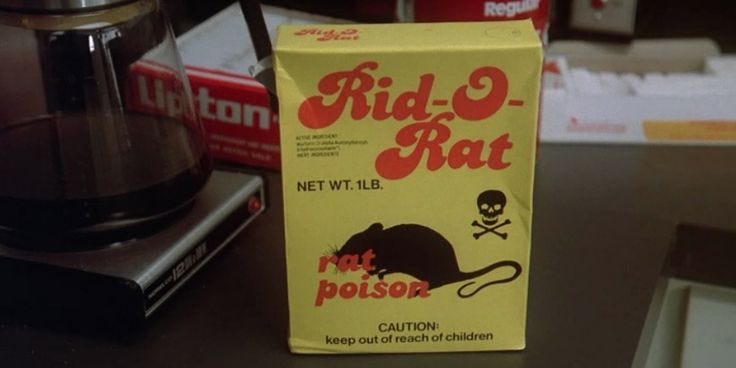

These treatments were administered in hospitals and made available by doctors, but they were also peddled as patent medicines, i.e. tonics, i.e. little bottles of liquor with some other stuff in them that you could get from the pharmacy. And of course, these same “active ingredients” were (and still are) common in other household stuff.

We’ve all seen 9 to 5, right? RIGHT?

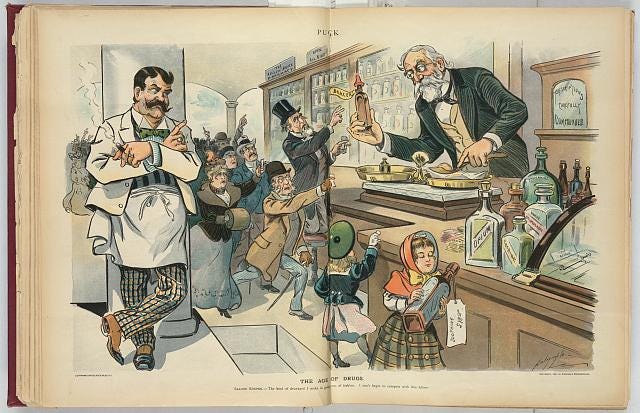

That availability meant it was easy for doctors — and um, non-accredited, non-educated, non-scientific interested parties i.e. quacks — to experiment with “tonics” in their own home. These “doctors” could try out different materials, swirl them together with opium or grain alcohol or both (was literally anyone ever sober during the Victorian era? Because the evidence seems clear…), put a label on, and then tell their local actual doctors and pharmacists that this was the good shit.

And they did.

Lest you think this is the stuff of legend, allow me to present some screenshots from the first-edition Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy (1899).

[The text-only view is here for folks with screen-readers who want to get into this wildness]

And while yes, cocaine and gold have both been known to snap me right out of a melancholy period, at this point, you might be wondering why. Like, what does poisoning a depressed person actually do? Don’t we already feel like we’re being poisoned by life and the air and the sunlight and basically everything? Isn’t depression its own special kind of poison?

You’re correct. However! The main reason that doctors would prescribe “nerve tonics” that contained deadline nightshade wasn’t because it made people feel better. It was because those depressants and otherwise incapacitating substances made people seem better. Caffeine and cocaine could pep someone up if they were low. Alcohol, opium, and arsenic could bring them down if they were manic.

In a blog post exploring the discovery of chocolate-coated strychnine tablets, VL McBeath wrote about finding out that a relative “was treated with liquid strychnia during a spell in a mental asylum.”

Why? McBeath theorizes that, because strychnine — a poison that is so lethal that it’s much easier to overdose than it is to administer an amount that doesn’t kill you — “stimulates the motor neurons…it [may have been] used to treat the psychomotor retardation that would have caused her slowness of speech, loss of appetite, loss of muscle strength and general listlessness.”

That doesn’t explain all of the unpleasant nerve tonics I’ve found, though. Like this one, whose main ingredient you may recognize as a very powerful herbal laxative. The only thing this tonic would rid you of is your bowels and, depending on where you are when it kicks in, your dignity.

But of course, that’s because at this time, people who were trying to market these products were really willing to put anything in them — and no one was around to stop them. Prior to controls on what could be sold (and what claims could be made by manufacturers, especially around health concerns), the weird uncles of the world could just mix up a batch of whatever they wanted and hawk to people in need. And because, again, these ingredients were common, the “cures” were readily available and pretty affordable.

Use as directed (which is to say, however you want)

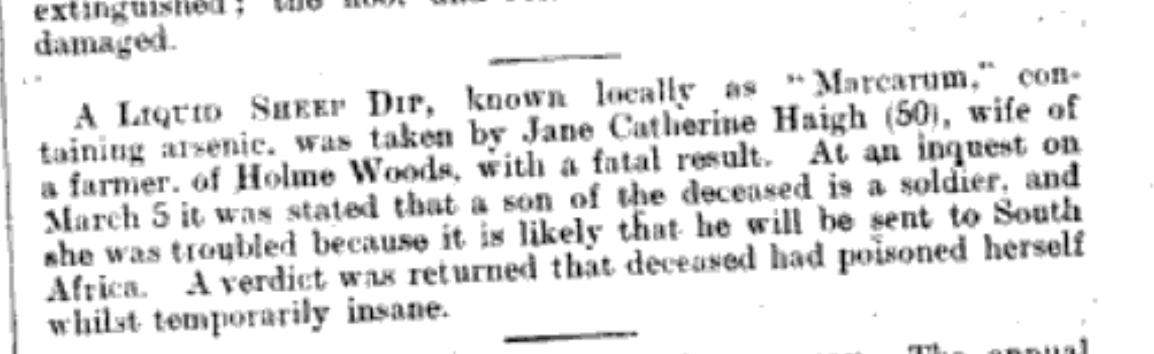

One interesting note is that people often seemed to die while attempting to treat themselves with the exact same kinds of treatments a doctor might have used. Whether it was chugging carbolic acid or taking a “sheep dip” (which is a kind of goo people dunked sheep in to make their wool nice, I think) in arsenic, whenever this happened, the entire medical profession managed one extremely nifty bob-and-weave move: They declared the death “suicide while temporarily insane.”

How strange that someone who was depressed might seek out a weed-killer whose active ingredient is arsenic! How unusual!

Now, probably some of these people really were trying to end it — and who could blame them? Living with a mental illness at a time when you’d just as soon be scrubbed with acid as you would be treated with anything that might work sounds truly terrible— but probably others were just going overboard on treatments they thought might work. After all, if a little bit works OK, maybe a lot works really well?

Eventually, of course, doctors (actual doctors) began to push for literally any kind of controls or government intervention. Patients were dying and pharmacists were using the free market as an excuse to hand them the syringe.

At the same time, there was a lot of concern about the role of food safety among governing bodies. Surely, you read The Jungle or at least knew about it in high school history?

The passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 (which basically said you couldn’t put non-food into things meant to be ingested) forbade the sale of so-called “patent medicines,” including the arsenic-laced nerve tonic and the chocolate-covered rat poison. Later, the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 picked up where Pure Food and Drug left off. The Narcotics Act didn’t actually ban the sale of narcotics and coca products, but it did tax them substantially, cutting back on the sale and production.

Between these two crucial pieces of legislation and the additional regulation on the pharmaceutical market (FDR’s Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 which, you know, meant you couldn’t call something “medicine” if it wasn’t actually medicine), the use of legitimate poison to treat depression and mania were relatively curtailed.

What’s interesting now, though, is how the grey market of wellness has started to harken back to the 1890s. I’ve never seen an influencer try to market belladonna as a cure for the Sunday Scaries, but it wouldn’t surprise me if some kind of ~moon juice~ or tincture that was being recommended on my Discover page did contain something that I would otherwise never ingest.

After all, supplements, especially those that make vague claims about mental health, are still an unregulated Wild West. But it’s probably fine, right?